The largest driver of gas demand, and subsequently storage, is the effect of temperature. While accurately forecasting weather several months in advance is not possible, it is possible to model the effects of different weather regimes on storage.

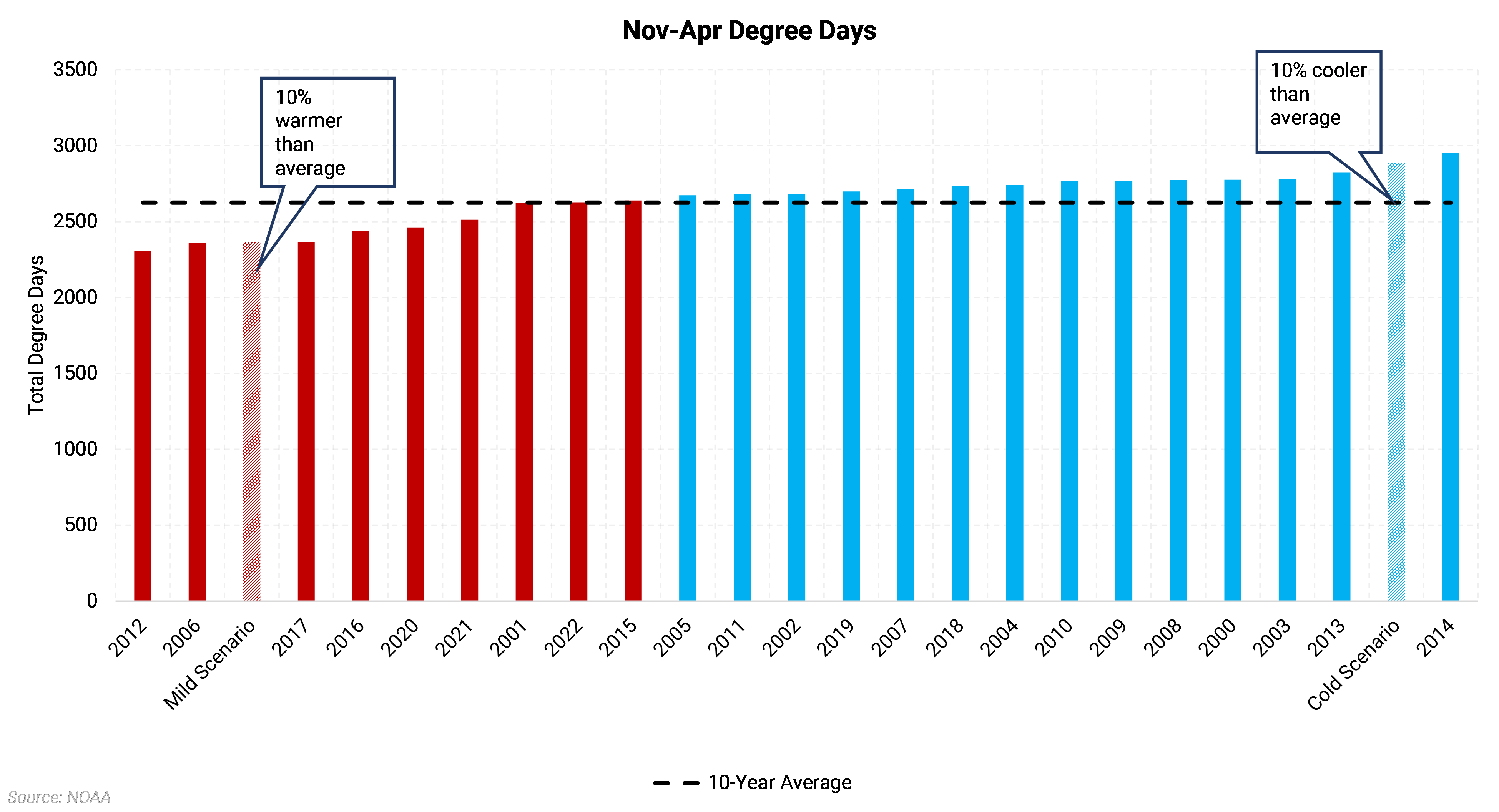

For this analysis, we selected three scenarios: a mild winter, a cold winter, and a base scenario. The base scenario uses the 10-year average weather, while the mild and cold scenarios use 10% more or 10% fewer degree days (a proxy for weather-driven demand) over November-April.

As shown in the chart above, the cold scenario would be the second coldest winter of the past 22 years, with only 2014 being colder. The mild scenario would be the third warmest of the past 22 years.

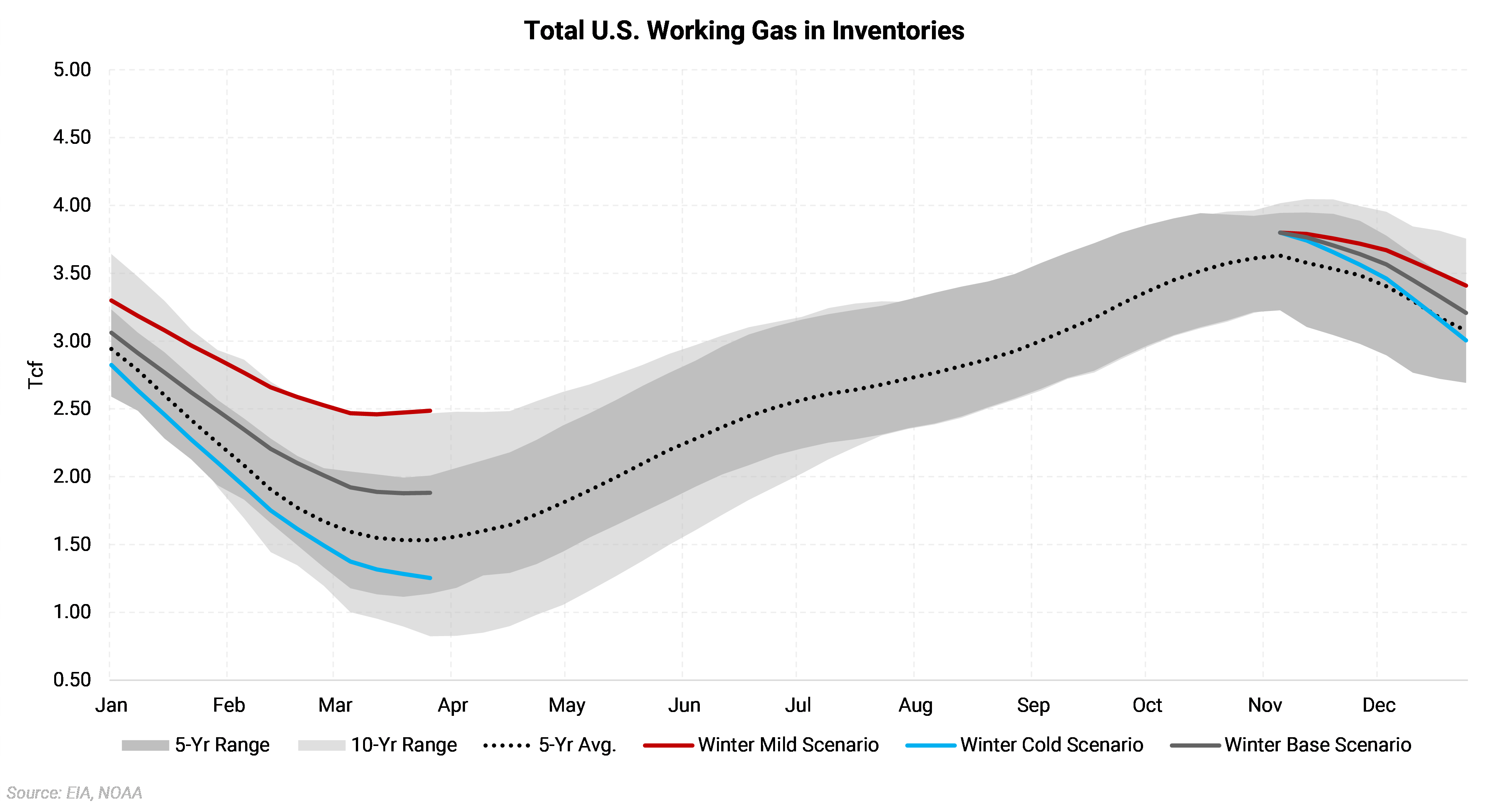

The chart above shows the results of the various weather inputs into our gas storage model. In this hypothetical example, we chose a starting point of 3.80-Tcf for Summer ’23 end-of-season estimate. We also have not adjusted for or factored in price changes. The base scenario results in an end-of-season estimate of 1.9-Tcf The cold scenario would put the winter end-of-season number at about 1.2-Tcf, which is at the lower end of the five-year range. However, the mild scenario would lead to inventories finishing winter at more than 2.5-Tcf, at the top end of the 10-year range, and more than 1-Tcf above the five-year average.

This exercise shows that a normal or warmer-than-normal winter season will likely lead to gas inventories finishing the winter withdrawal season well above the five-year average. Even a winter that comes in as the second coldest of the past 22 years would only tighten inventories to about 300-Bcf below the five-year average.

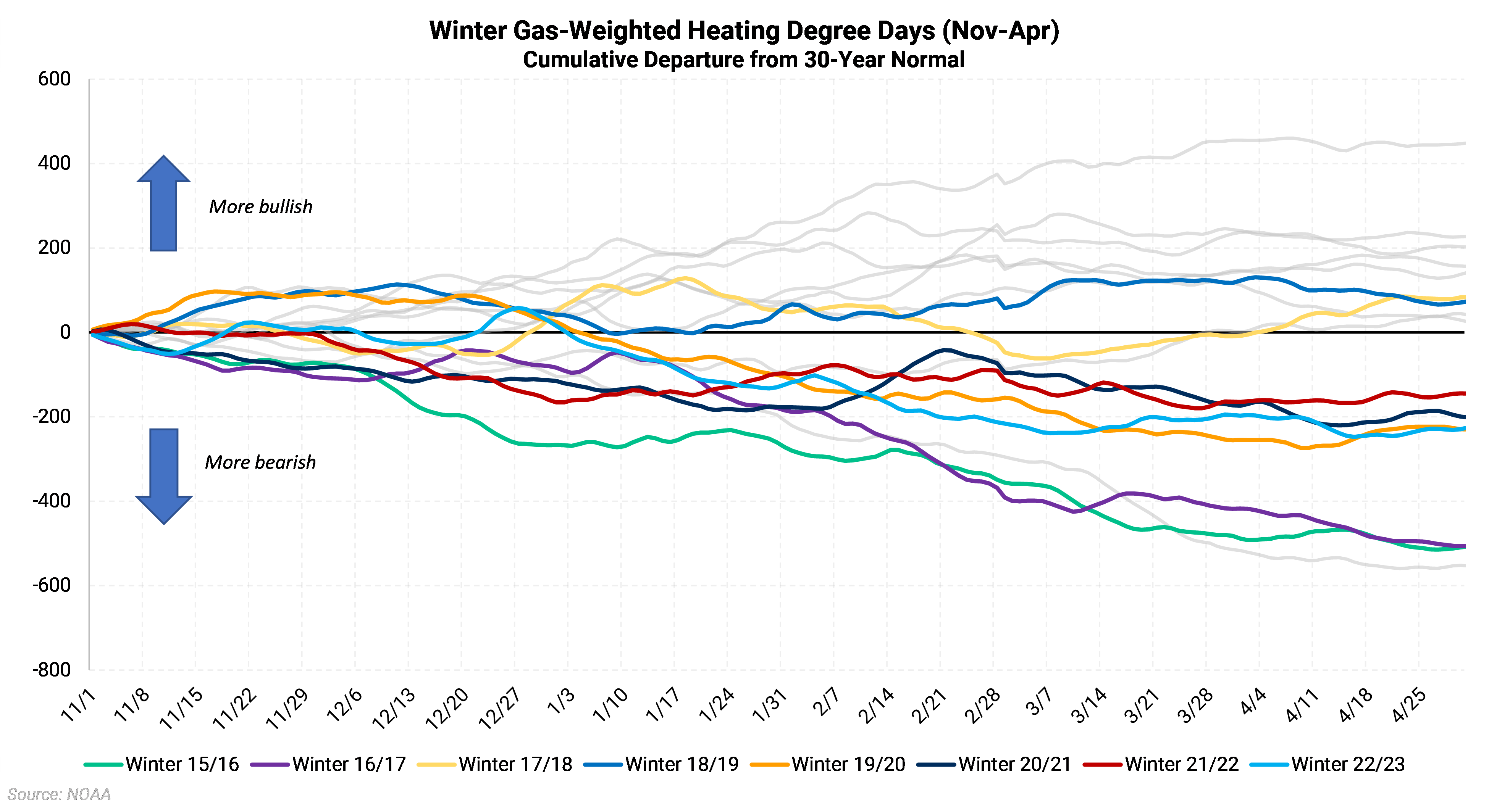

When looking at weather empirically, winter seasons have trended warmer in recent years, lowering the probability of a colder-than-normal winter. The chart above shows the cumulative number of gas-weighted heating degree days for the last 22 years. Of the previous eight years, only two were colder than normal. This is not a prediction of future weather, only identifying a trend that winters have, on average, been warmer.

We view the Cal’ 2024 natural gas strip as being risked to the downside, especially if the weather is below average. With no additional demand growth and production still expected to rise, weather-driven demand will need to come in much stronger than average to move the gas market out of oversupply sufficiently.